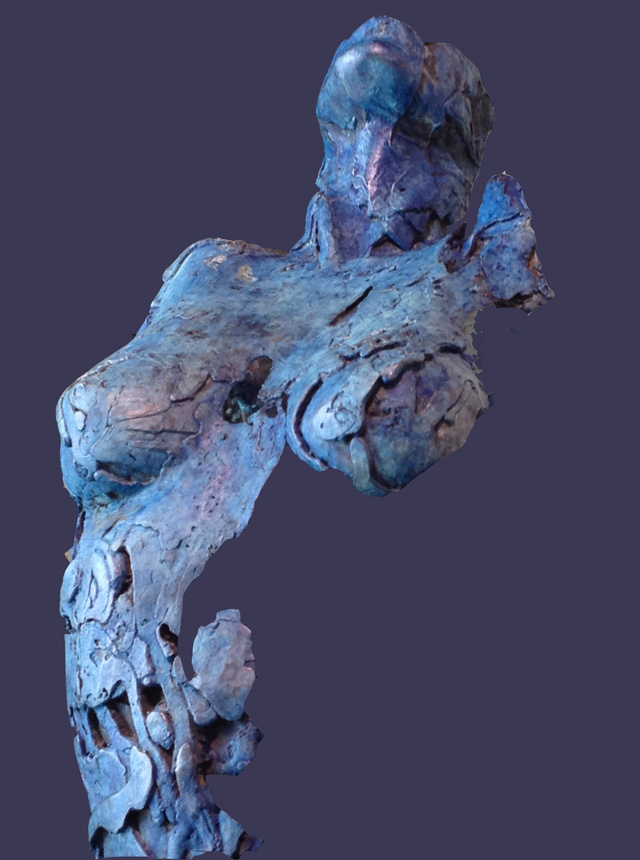

In viewing the Impressionist & Modern sale at Christie’s in London a couple of weeks ago, I saw a piece by Archipenko and couldn’t help but get lost in a ‘Cagean’ state of mind; a world in which art and love co-exist in the bliss of both laughter and silence.

Archipenko’s use of negative space, seems so completely analogous to John Cage’s silence, where time and space just ‘are’.

They don’t require a form of representational matter to exist, they simply ‘are’ and exist within their rightful place.

Like love, silence and negative space are invisible to the eye, yet of equal importance.

As Maria Podova states in her review of Kay Larson’s book Where the Heart Beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism and the Inner Life of Artists, [1] negative space “…isn’t nihilistic, isn’t an absence, but, rather, it’s life-affirming, a presence.

Cage himself reflects:

‘Our intention is to affirm this life, not to bring order out of chaos, nor to suggest improvements in creation, but simply to wake up to the very life we’re living, which is so excellent once one gets one’s mind and desires out of its way and lets it act of its own accord.’” [2]

Archipenko inscribed in the clay on ‘Walking’ (the sculpture that triggered this blog): ‘apres moi viendront des jours quand cette œuvre guidera et les artistes sculpteront l’espace et le temps’ (After me the days will come when this piece will serve as a guide and the artists will sculpt space and time). [3]

The poetry behind this inscription felt like a message in a bottle announcing the changes in the conventional concepts of sculpting.

In a complete reversal of the acceptable space surrounding solid sculpture, Archipenko’s human figure substituted limbs with ‘voids of free space’. [4]

John Cage sculpted using notes and rests.

While his Ophelia, a ‘two-tone poem to madness’ should never even have been there in the first place, it was potentially, an important part of his emotional growth.

Like a note and a rest, like positive and negative space, it simply ‘was’.

If we can accept that, then we might be able to bring the unconscious and the conscious together, tearing down the walls that keep us prisoners of the ego.

We might find that there is no need for kenophobic tendencies.

There is only full and empty.

The solutions lie in simply ‘being’, which allows for ‘creating’.

One can almost hear Schoenberg questioning Cage on all the possible solutions to a counterpoint question.

After all the options were exhausted Schoenberg asked him: What is the principle underlying all of these solutions?

“…it occurred to me (Cage) through the direction that my work has taken, which is renunciation of choices and the substitution of asking questions, that the principle underlying all of the solutions that I had given him was the question that he had asked, because they certainly didn’t come from any other point. He would have accepted the answer, I think. The answers have the questions in common. Therefore the question underlies the answers.” [5]

Writen by Boky Hackel

1.http://thepenguinpress.com/book/where-the-heart-beats-john-cage-zen-buddhism-and-the-inner-life-of-artists/

2.https://www.brainpickings.org/2012/07/05/where-the-heart-beats-john-cage-kay-larson/

3.http://www.christies.com//lotfinder/sculptures-statues-figures/alexander-archipenko-walking-5971056-details.aspx?from=searchresults&intObjectID=5971056&sid=08024641-ee18-46b4-886c-fbcd952fb9d9

4.http://the-artifice.com/alexander-archipenko/

5.https://www.brainpickings.org/2012/07/05/where-the-heart-beats-john-cage-kay-larson/